The Name Game: How First Names and Nicknames Confuse Genealogical Research

When it comes to genealogy, names can be both a gift and a puzzle. Family naming traditions in the 18th and 19th centuries followed recognizable patterns; however, the use of nicknames, recycled names, and cultural influences often complicates the search for ancestors. What appears to be a simple name in a census record may actually conceal a complex story.

FIRST NAMESNICKNAMESGIVEN NAMES

Wayne Karl Driver

10/7/20254 min read

A Personal Challenge

While researching my paternal family, I often found myself lost in the complexities of first names and nicknames. I discovered 16 different variations of individuals named Samuel, 15 Roberts, 14 Williams, 13 Mary's, and 12 Johns.

By 1900, new names like Donald, Edward, Kathleen, and Richard began to appear. Yet to this day, I remain hesitant to say with confidence who was who. Sometimes nicknames help, but they are rare.

“So, was there madness to the naming approaches in the past? Let’s see.”

Family Naming Patterns

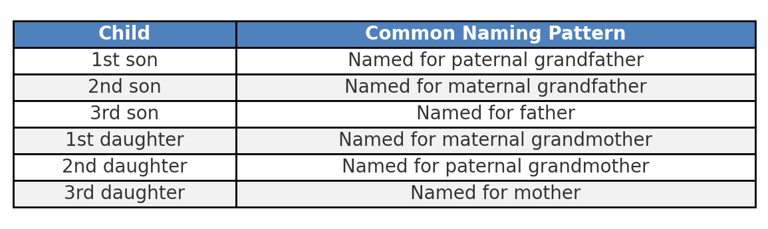

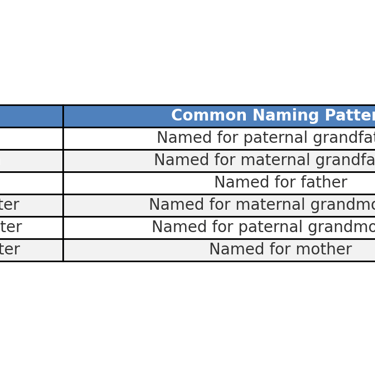

In many communities, families followed unwritten rules:

Typical 18th–19th Century Naming Order

This system helped preserve family heritage, but it also meant many cousins within the same generation shared identical names. A neighborhood might have three Johns and four Mary's — all related but easily confused.

Nicknames & Variations

The trouble deepens when we add nicknames. Many names we take for granted today had multiple short forms in the past:

Elizabeth → Lizzy, Betsy, Bess, Eliza, Beth, Libby, Betty

Margaret → Maggie, Peggy, Meg, Greta, Daisy

William → Will, Bill, Liam

Edward/Edwin → Ed, Eddie

Robert → Rob, Bob, Bobby

Sarah → Sally, Sadie, Suky

Mary → Polly, Molly

John → Jack

“A census might list Polly while a marriage record lists Mary — leaving the impression of two different women when it was the same person.”

The Surname Twist

Families also often used surnames as given names (e.g., Taylor, Jackson, or Carter). For genealogists, this creates confusion: Was “Jackson” a first name honoring a mother’s maiden name, or was it a surname misrecorded as a given name?

African American Naming Practices

For African Americans, naming carried even deeper meaning. During slavery, names were often chosen or imposed by enslavers, but families preserved cultural identity and dignity through naming traditions. After emancipation, many African Americans asserted their independence by:

Choosing patriotic names like Washington, Jefferson, Madison, and Lincoln.

Honoring leaders and role models with names like Frederick (for Douglass) or Booker (for Booker T. Washington).

Elevating surnames into first names to mark a break from the past — e.g., Grant or Clay.

Reclaiming Biblical strength with names like Moses, Joshua, or Esther.

“A child named Lincoln or Douglass wasn’t just given a name — they were given a legacy.”

These choices spoke volumes about resilience, vision, and the desire to tie one’s identity to a greater story of liberation and possibility.

The Birth Order Nicknames

Not all names came from the Bible, family trees, or famous leaders. Some were born right inside the household. Families in the 18th and 19th centuries often gave affectionate sibling-based nicknames that reflected a child’s place among brothers and sisters.

Common Birth Order Nicknames:

Bubba / Buddy / Brother – Often the oldest son, the protector.

Sissy / Sister – Eldest or only daughter.

Junior / Sonny / Little [Father’s Name] – Used when a son was named after his father.

Buster – A favorite for the youngest boy, especially the “baby of the family.”

Baby / Babe – The youngest child, regardless of gender.

Sis / Bro – Everyday nicknames that sometimes stuck for life.

“Not all names came from the Bible or family trees — some were born right inside the household.”

A Personal Story: Bubba and the Mystery of Hobart

I will never forget the day I found out that my grandfather had an additional birth name. I thought his formal name was EDWIN DOUGLAS DRIVER and his nickname was “Bubba.” Then I stumbled across the 1910 census, where I found a boy listed as Hobart D. Driver — the same age as my grandfather.

I was puzzled. Who was this new person? Was he another brother who had died young? Or was this simply a misspelling?

The puzzle was solved when I visited my grandfather’s brother, my Godfather, ELIJAH MORRIS DRIVER, affectionately called “Buster.”

“The puzzle was solved when Uncle Buster smiled and said the name was actually Hobart — and it was my grandfather.”

At some point, my grandfather dropped the name Hobart and went by Edwin Douglas.

Further research revealed that Hobart had a spike in popularity around 1901 — right when my grandfather was born. His parents may have been caught up in this new trend, even though it broke with the usual family pattern. If they had followed tradition, my grandfather, the oldest son, should have been named after his paternal grandfather, Addison Driver. Interestingly, Uncle Buster, the second son, did follow tradition: he was named after his maternal grandfather, Elijah Morris.

📌 Naming Trend Alert

The popularity spike of Hobart and McKinley followed the deaths of Vice President Garret A. Hobart (1899) and President William McKinley (1901).

Families across America, including African Americans, chose these names to honor national leaders, express patriotism, and align their children with the spirit of the times.

This story reminds me that naming conventions are guidelines, not rules. Families made choices, experimented with trends, and sometimes broke tradition altogether — leaving us, their descendants, to piece together the puzzle.

Why It Matters for Genealogists

Understanding naming conventions helps researchers avoid false leads. Some common pitfalls:

Assuming different nicknames = different people

Missing maternal surnames hidden in given names

Overlooking recycled names after a child’s death

Anglicized names masking immigrant origins

Misreading African American “honor names” as random when they carried cultural and political weight

Genealogy Tip

Always cross-check:

Look for clusters of family members (neighbors, witnesses, church registers).

Compare nicknames in family letters or oral histories with official records.

Pay attention to middle names — they often preserve maternal or ancestral surnames.

Recognize political or cultural references in African American names; they may reveal the time period or social movements inspiring a family.

Closing Thought

“The Name Game isn’t just about confusion — it’s also about clues.”

Every repeated name, every surprising nickname, every borrowed surname or honorific tells us something about family priorities, cultural values, and historical context. Decoding the “game” reveals not just names, but the aspirations and identities of those who carried them.

Connect With Us

To stay informed about the latest research and discoveries, connect with us on our social media channels.

© 2025. All rights reserved.

Let's Keep In Touch